by Joan Darby

It’s hard to imagine the excitement of the Richmond settlers as they experienced the first spring in their new community. Owning land had been no more than a dream for most of the disbanded soldiers of the 99th/100th regiment, so the offer of free land in a new country was an irresistible lure to stay in Canada at the end of the War of 1812. Now they faced the challenge to succeed in this new venture.

photo courtesy

Hamilton College Library Digital Collection

When they accepted the government’s offer of free land, the soldier-settlers were each given a year’s army rations, the tools to succeed in settling their land, and seeds for their future. Few other British emigrants had the luxury of a year’s supply of free food before having to provide food for themselves and their families. The spring of 1819, the first spring on their land, would not have been as crucial or challenging with this safety net in place. We do not know what seeds the settlers were given for their first crops but they were likely the basics. Typical of the time would have been carrots, turnips, onions, potatoes and grain. But once this first year of support was ended, what resources did the settlers have for food and crops?

Many emigrants to Canada brought seeds from “home” or saved seed from earlier crops. This was not the case for the settlers from the 100th regiment, who had traveled extensively throughout the war and who had been provided for by the military establishment. Once the year of rations in the new settlement ran out, they turned to the new store, opened around the fall of 1819 by Lt. George Lyon, for the seeds to plant their crops and the vegetables that would feed their families.

What seeds were available at Lyon’s Store?

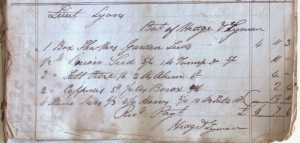

first seed order

All of Lyon’s seven seed orders in the period from 1820 to 1825 were placed through Hedge & Lyman, a company which had existed in one form or another in Montreal since 1800. Although their primary business was hardware and pharmaceuticals, Hedge & Lyman appear to have acted as distributors for many other commodities. Each seed order was placed in March of the year in order to take advantage of the easiest – and cheapest – shipping season, and to have seed available in time for spring planting. After 1825, there are no further orders for seeds or plants in his invoice book. Lyon operated his store for almost 20 years more; why did he not order seeds again?

courtesy Hamilton College Library Digital Collection

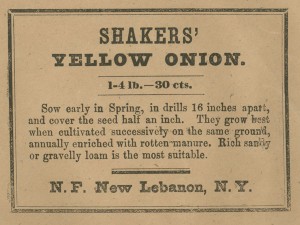

George Lyon’s first seed order, for which the date is unreadable but which was likely in the spring of 1820, was surprisingly small: ½ box of onion seed, a quantity of turnip seed, and a box of “Shakers Garden Seeds”. Since the late 1700’s, the United Society of Believers, or Shakers, had run one of the leading seed-raising enterprises in North America and distributed their seeds to merchants in the American states. Their seeds had the reputation of being “the best in America”, so it is in keeping with the calibre of the community that George Lyon purchased the first seed order for Richmond from such a prominent and well-respected source.

The March 1821 order was the largest of any of Lyon’s seed orders. It included seeds for food staples such as carrots, onions, peas, beans, turnips, radishes, cabbage, lettuce, beets and turnips; culinary and medicinal herbs such as [lemon] balm, sage, caraway, parsley, summer savory, saffron, and pepper grass; and a quantity of clover. It is surprising that Lyon ordered “saffron”. Saffron itself would have been a highly expensive luxury, so this would more likely have been safflower, a substitute for saffron that was used for cooking, dyeing and in the treatment of ague, a malaria-like illness common among early settlers. It’s difficult to explain the omission of an order for any of the major grain seeds or for winter squash or corn, two crops that were frequently grown in the American states and both Upper and Lower Canada at the time. We can speculate that the farmers were able to save seed from their grain crops of 1819, grown with the seed given them as part of their settlement rations. However, other crops for which seed is easily saved, such as peas and beans, were still included in Lyon’s 1821 order. Perhaps there was enough for the settlers to do without the extra work of saving this seed?

Seed orders from 1822 through to 1825 were much smaller, and “back to basics”: turnips, radishes, cabbages, onions and clover. These were crops from which it was difficult to save seed. It is surprising that, during this entire period, there was only one order for lucerne (alfalfa), a common field crop. Often early settlers sent “home” for lucerne seeds to be sent to the New World; it was an important crop.

Most of Lyon’s seed orders were for “papers” of seed – packages of some sort. Prior to the Shakers seed enterprise, most seeds were sold by weight or volume and often did not survive being transported, either because of rot and mildew, or destruction by pests. The Shakers began to package seeds in papers, but we have no information about the quantity in each paper or whether, as with today’s packages of seed, the quantity varied. Lyon ordered clover in quantities ranging from 10 papers to 50 pounds. Turnips, another staple field crop for animal feed as well as human consumption, were ordered in quantities ranging from 2 papers to 3 pounds.

Montreal Fruit Nursery:

Montreal

courtesy

http://montrealhistory.org

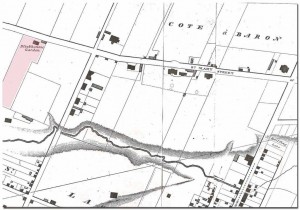

The most interesting of Lyon’s seed and plant orders was placed in October of 1823 with the prestigious Robert Cleghorn of Montreal. From the very early 1800s, Cleghorn operated a nursery specializing in fruit trees and plants, and was well known and respected not only throughout the Canadian colonies, but also in the United Kingdom. The 1825 atlas of Montreal shows Cleghorn’s Blink Bonny Nursery highlighted in red on the map, although the publisher of the atlas did not deign to identify many other properties, even that of Cleghorn’s neighbour, James McGill, founder of McGill University. Cleghorn obviously was a businessman of some importance. At a time when settlers frequently established their orchards by “domesticating” wild apples, plums, gooseberries, currants, strawberries and raspberries, or by purchasing inexpensive scions to graft onto wild trees, George Lyon placed a huge order for fruit trees and plants. This one order is for apple trees, both young “whips” and more mature trees, in addition to 20 trees of “cyder apples”, cherry trees, plum trees, gooseberries, currants, white raspberries and choke cherries – 62 trees and 45 plants in total. This is surprising in many ways: the expense of shipping not only the young whips, but especially the more mature trees, must have been considerable; Lyon paid a Mr. Lean to select the trees; Lyon specified white raspberries, which were much more expensive and fragile. He spared no expense and went to the best source. For whom was Lyon ordering these fruit tree

British Colonist

September 7 1852

We can speculate that much of this order for fruit trees was destined for Lyon’s own estate. When Lyon’s property was being sold off in 1852, the notice of sale described a “large dwelling House on the premises, with Garden and Orchard attached.” Lyon was part of the Richmond “gentry” and his lifestyle reflects that. However, compared to the estates of the elite in southern Ontario, such as those at York, Lyon’s garden and orchard are more productive than pleasure gardens. For example, there are no orders for ornamental trees, shrubs or plants, which were common purchases in the more established communities such as York.

The invoice book for the early years of George Lyon’s store in Richmond is a fascinating look at life in our community in its first years, and hints at the differences between the “civilian” settlers, the average soldier-settlers and the “gentry”.

Sources :

- Account Book of George Lyon’s Store. City of Ottawa Archives.

- Cross, Michael S. “The Age of Gentility: the formation of an aristocracy in the Ottawa Valley.” Historical Papers, vol. 2, no. 1, 1967.

- Curry, John. Richmond on the Jock. Stittsville: Stittsville News, 1993.

- Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=4032

- Henderson, Robert. “Former occupations of regular soldiers during the War of 1812.” http://www.warof1812.ca

- Martin, Carol. A History of Canadian Gardening. Toronto: McArthur, 2000.

- McCalla, Douglas. “A World Without Chocolate: Grocery purchases at some Upper Canadian Country Stores 1808-18161.” Agricultural History vol. 79, no. 2 Spring 2005.

- “Chairman of the Board observes Jubilee.” Montreal Gazette June 10, 1939, p. 2.

- “Robert Cleghorn”. Quebec Heritage News Nov.- Dec. 2009. http://montrealhistory.org

- Roberts, A. Barry. For King and Canada. Goulbourn Township Historical Society and Museum, 2004.

- von Baeyer, Edwina and Pleasance Crawford, eds. Garden Voices: two centuries of Canadian Garden Writing. Random House, 1995.

- Welch, Edwin. “A Pioneer Store in Upper Canada.” Ottawa 1982. Unpublished manuscript written for the Historical Society of Ottawa. City of Ottawa Archives, A2009-0137 Box #2, #3 D04, ABUS 19.

- Woodhead, Eileen. Early Canadian Gardening. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998.

One Response to Seeds for the Future – Gardening in the 1820’s